For years, universities in Indonesia have measured their success by graduation rates. The higher the percentage of students who graduate on time, the better a university is perceived. But here’s the problem: this system often prioritizes efficiency over quality, leaving many students unprepared for the realities of the job market.

According to data from the World Economic Forum, two crucial skills are essential for the future workplace: (1) AI and big data, and (2) leadership and social influence. While AI and big data were almost nonexistent on this list five years ago, leadership and social influence have significantly risen in importance. This tells us something important—some fundamental skills will always be necessary, no matter how much technology advances.

The Silent Killer of Creativity in Indonesian Universities

When we look at the list of in-demand skills, two things stand out: analytical thinking and creative thinking remain at the top. This is no surprise. These are the skills that AI cannot replace. Yet, ironically, many university systems in Indonesia suppress these very abilities through rigid accreditation requirements that emphasize graduation rates over actual learning.

Think about it: students are evaluated based on their ability to complete their studies on time, not on their capacity for critical and creative thinking. Grades are often a reflection of exam scores rather than true understanding. Many professors, perhaps out of kindness, are generous with high grades, leading to an overflow of students graduating with honors. But what does this really mean? If we are not fostering the right skills, are we truly preparing students for success?

The Problem with Memorization-Based Learning

Another significant issue is the way most university exams in Indonesia are structured. The easiest cognitive skill to assess is memorization—simply recalling information. That’s why many universities still rely on multiple-choice tests. They are quick to grade and provide clear numerical results, making them convenient for accreditation systems. But memorization alone does not build problem-solving skills, innovation, or the ability to think independently.

Meanwhile, assessing analytical and creative thinking is much more complex. Essay-based assessments require time to grade, and there is always an element of subjectivity involved. This makes them less appealing in large-scale educational systems that prioritize efficiency over depth of learning.

The Fear of Being Wrong in the Classroom

Another major obstacle to developing critical thinking is the classroom culture itself. Many students hesitate to voice their opinions because they fear making mistakes. This fear is deeply ingrained. A former government official in Indonesia once made an insightful comparison: “In some countries, people are free to do anything except what is forbidden. Here, people avoid doing anything unless explicitly allowed.”

This mindset creates a passive learning environment where students prefer to stay silent rather than risk giving the wrong answer. They are afraid of being judged, afraid that their grades might suffer if they challenge the status quo. This, in turn, discourages independent thinking and innovation.

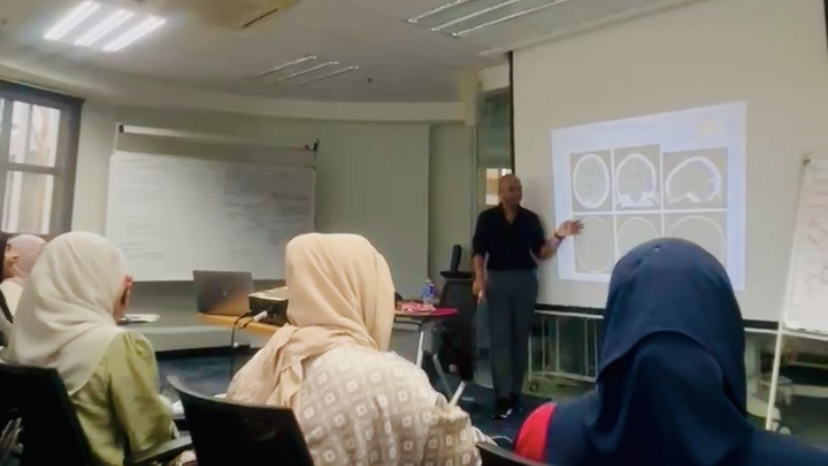

The Role of Professors: Encouragement Over Instruction

So, how do we fix this? One possible solution is to shift the role of professors from mere knowledge providers to facilitators of critical discussion. Instead of delivering long lectures, educators should focus on encouraging students to think, question, and engage in meaningful dialogue.

A simple way to achieve this is by replacing monologue-style teaching with the Socratic method—a teaching technique that encourages learning through questioning and discussion. This method forces students to analyze information critically and formulate their own arguments rather than passively absorb facts.

Some professors may feel uncomfortable with this approach, especially when faced with exceptionally bright students who challenge their perspectives. But true education is not about maintaining authority; it is about fostering curiosity and intellectual growth. Professors should not see intelligent students as a threat but as an opportunity to elevate discussions and refine their own understanding.

The Neuroscience Behind Critical Thinking

From a neuroscience perspective, two critical brain regions influence analytical and creative thinking: the prefrontal cortex and the limbic system.

- The prefrontal cortex is responsible for logical reasoning, creativity, imagination, and critical thinking.

- The limbic system regulates emotions, including fear and anxiety.

Here’s where it gets interesting: the prefrontal cortex and the limbic system do not function well together. When emotions like fear or anxiety take over, rational thinking is suppressed. This is why people struggle to think clearly when they are stressed or afraid.

Now, imagine a classroom where students are constantly worried about being wrong. Their limbic system is in overdrive, making it nearly impossible for their prefrontal cortex to engage in deep thinking. If we want students to develop critical and creative thinking, we must create a learning environment where they feel safe to make mistakes.

Fight or Flight: The Hidden Battle in Every Classroom

From an evolutionary perspective, humans have two basic responses to challenges: fight or flight. While some people naturally rise to challenges, most instinctively avoid risks, especially if failure comes with negative consequences.

Now, apply this to a typical classroom setting in Indonesia. When a professor asks a question, what is the safest response for a student? Silence. Saying “I don’t know” is often seen as a way to avoid embarrassment or judgment.

This is where educators have a responsibility. They must create classrooms where students feel comfortable expressing ideas without fear of being ridiculed or penalized. Encouraging open discussions, valuing diverse perspectives, and reinforcing the idea that mistakes are part of learning can make a huge difference.

A Call for Change

The good news is that change is possible. Universities in Indonesia can—and should—foster analytical and creative thinking. But systemic challenges remain. Accreditation systems still emphasize graduation rates, and traditional assessment methods continue to favor rote memorization over real intellectual engagement.

If we truly want to prepare the next generation for the future, we need to be brave enough to challenge the status quo. As educators, students, and policymakers, we must push for a system that values not just the quantity of graduates but the quality of their thinking.

The world needs more problem-solvers, innovators, and leaders who can navigate an increasingly complex future. And it all starts in the classroom.

What do you think? As students and educators in Indonesia, how can we work together to create a better learning environment?